For many years now, I’ve spent a fair amount of time in local school sixth forms (helping to run this). One thing that surprises me about schools today is how few of them teach economics. While it’s true that you don’t need an economics degree to run a business, some of the theory will help you.

Supply and demand is one of those things that even people without an economics background can grasp quite easily, and if they think about for a bit, can probably work out. But if you understand supply and demand in the way that economists do, you’ll be able to understand slightly more advanced concepts like elasticity, which will be directly relevant to your business. More on elasticity in ‘Important Economics Concepts Every Businessman Should Know, Number 3: Elasticity’…

So:

Important Economics Concepts Every Businessman Should Know, Number 2: Supply and Demand

We’re in the realm of microeconomics here, although for once we aren’t talking about the individual consumer or the individual supplier. We are in fact talking about lots of them.

2a: The Demand Curve

Go into HMV and have a look at all the music CDs you can buy (no seriously, go and do this while you still can). Maybe you’ve done this recently – some maiden aunt gave you a £20 HMV voucher for Christmas and you’ve wondered what to spend it on (and in fact whether or not they’ll take it…). You went in with your £20 voucher and a credit card to buy some CDs. How many CDs would you buy? That will depend on things like how much you like music and on the price of the CDs you were interested in.

To make this simple, let’s assume that all CDs in HMV cost the same, but that at the moment, because you haven’t reached the store, you don’t know how much. Let’s further assume that HMV sells all the music you could be interested in. If I asked you how many CDs you would buy if CDs cost £5 each, you would be able to answer. Maybe (with your £20 voucher in mind), you would say “four”. And if they cost £10 each, you’d perhaps say “two”. And if they cost £1 each, you’d say “forty” (because at that price you’d spend more than the voucher). You can see that there is a relationship between price and how many you want to buy – a relationship you could plot as a curve:

(Yes, I can see that’s actually a straight line. Economists still call it a curve. They just do.)

See how at higher prices, this consumer demands lower quantities. It’s a straight line relationship for this individual, but that won’t always be the case.

That’s not actually very interesting. Where it gets better is when you add up everyone’s demand curves to make an aggregate demand curve. OK, that’s still not hugely interesting. What you need to do is combine the aggregate demand curve with an aggregate supply curve.

2b: The Supply Curve

Now let’s think about the suppliers. In the retail market for music CDs, the suppliers are the likes of HMV (and Amazon etc). HMV has its own suppliers – the music publishers. How does HMV react to changes in the price they charge for CDs in the shops? In other words, at a given price, how many CDs will HMV put on sale in their shops?

Let’s assume that HMV can sell CDs for £10. At this price, they will put x CDs on sale in their stores. If the retail price was £20, they would make more per unit sold, and so it follows that they would want to sell more – perhaps they would devote more of their shop floor space to CDs and less to DVDs, perhaps they would open new stores etc. If the retail price was just £1 (competition from downloads perhaps), then possibly HMV would make a loss on each CD they sold and they wouldn’t want to sell any CDs.

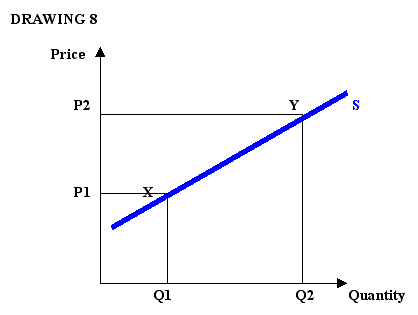

So again you can see that there is a relationship between price and quantity supplied. And again, you can plot this relationship as a curve:

Once again though, what we really want to do is add up the supply curves of all the suppliers (and potential suppliers) of music CDs to make an aggregate supply curve. (Why potential suppliers? Well, if the price goes up, maybe other companies will enter the market. Perhaps someone will set up a new rival to HMV.)

You’ll notice that while the demand curve slopes downward, the supply curve slopes upward. Logically, there is an intersection between the two curves at a certain price / quantity combination. This combination is the equilibrium price.

2c: The Equilibrium

The equilibrium price has special qualities, but how special those qualities are depends on the nature of the market – specifically how competitive that market is.

Markets can be more or less competitive. A market with only one supplier, where that supplier is able to do what they like in terms of price and quantity supplied is not very competitive at all. A market where there are lots of suppliers vying for lots of customers’ money all selling very similar (or identical) products and who cannot prevent even more suppliers from entering the market is very competitive.

If a market was perfectly competitive, then the price and quantity sold would be the equilibrium – the intersection of the aggregate supply and aggregate demand curves. Why? Well, think about it…

Let’s assume the price of something starts at £8. If one supplier sold at £9, nobody would buy from that supplier since there are plenty of cheaper suppliers around selling identical goods. So could a supplier sell at £7 and corner the market? In fact, what if one supplier could reduce the price as low as £6 if it really wanted to, and still stay as profitable as it needs to warrant staying in the market? Don’t forget that this is perfect competition – all the suppliers are the same.

Therefore, if supplier A drops the price to £7, all the other suppliers are going to have to follow if they want to sell anything. In fact, one supplier will go as far as £6 (but no lower) and then they all will.

So what happens in perfect competition is that the market price quickly (in fact instantly) drops to the lowest point at which suppliers still find it worth being in the market. Which is great for consumers.

Thing is, perfect competition is pretty much a theoretical ideal rather than something you find in the real world. Some markets are certainly more competitive than others. But it doesn’t necessarily follow that making an imperfectly competitive market more competitive is a good thing to do*.

Anyway, that’s the basics of demand and supply curves. Where it gets interesting for your business is when we get on to elasticity.

* Consider if you could make music retail perfectly competitive. That would probably involve removing things like CD production plants from the process, and contracts with music publishers. If you take away contracts with music publishers then presumably there’s no reason for the publishers to pay rock stars lots of money.

In that scenario, then perhaps all consumers can get their music for free or almost free (via download perhaps) because the equilibrium price will be the price at which it is still worth suppliers being in the market. Since the cost of supplying each extra track (the ‘marginal cost’) is pretty much negligible, there will always be someone prepared to offer a particular track for free. The market is much more competitive than one dominated by HMV and Amazon. But is society improved? Consider:

Consumers can get all the music they want for a negligible outlay, but…

Music retailers go out of business. Shop assistants are unemployed.

Music publishers go out of business. Music industry A&R guys are unemployed.

There is no way for rock stars to make money out of recorded music, so many future rock stars become economists instead and the world misses out on all the great music they might have recorded.

So while you can afford to buy that Jive Bunny Greatest Hits CD you promised yourself, you’ll miss out on great music in the future and you’ll feel guilty that all those HMV shop assistants are now out of work…